Miroslav Pudlák, Petr Bakla:

Czech Composers in the Post-Modern Era

Czech Music 1/2007

(EN) - excerpt

(...) Martin Smolka (1959) is the only one of the composers mentioned to have a solid footing in the international context. From his student years he followed his own temperamental and aesthetic tendencies in a self-conscious way, seeking to define his own musical originality. He then systematically based his musical language on his introspective insights. It is a language dominated by slow tempos, "detuned" consonances, a dreamy, melancholic mood, and playfulness in the use and treatment of unusual sounds. Smolka is another who started out as a "home" composer of the Agon Ensemble. Commissions from festivals like the Warsaw Autumn and Donaueschingen as well as distinguished ensembles and interpreters soon made him the leading representative of his generation of Czech composers abroad. (...)

Interview with the composer by Petr Bakla:

Petr Bakla: The text in the CD booklet says something about the sources of your music and the point it has reached. After more than 20 years of active composing, do you have a sense of the way in which your music will develop in the future? What attracts you?

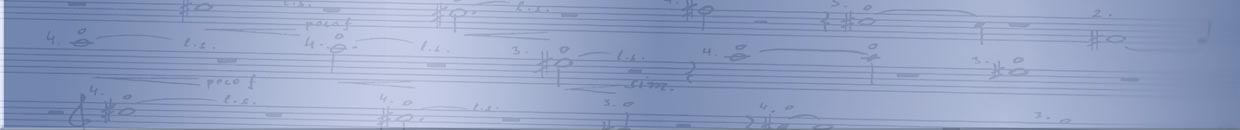

Martin Smolka: To answer directly I would have to describe dreams and desires and all kinds of plans with very unclear outlines. And that is unreliable. The history of my last larger work, Semplice, is a good example. I had found four poems-prayers by various medieval and modern mystics and for ages I was thinking in terms of a monumental oratorio. Gertrud von le Fort, fascinating visionary verses such as "God of Flame-Throwing Mountains" were to be the axis. Then in a moment of high creative pressure I wrote a letter to Armin Köhler, the programme head of the Donaueschingen Festival, asking if he could advise me where to turn to get a chance of having the planned piece performed – somewhere where I could get and orchestra and choir, and perhaps an ensemble for early music. He surprised me by accepting it into his plans for Donaueschingen, and later he surprised me again by having a completely different idea of it. What attracted him was the notion of combining old and new instruments, while the singers were fading out of the plans. Then when I got my hands on verses in the original languages, I discovered that they inspired me less, and there were long-drawn out inquiries (never complete) about whether I could obtain permission to use the texts (of the modern verses), and meanwhile I was working on other things and my enthusiasm about the flame-throwing mountains quietly cooled off. Eventually, after three years of dreaming and half a year of intensive work, Semplice turned out amazingly well: it's a long piece, it was played superbly to a concert hall full of experts and connoisseurs – I have something to be happy about. But in fact it was not at all what I had been wanting to aim for in the beginning and what had attracted me then. Instead of visionary monumentality it was more about delicate colour shades and subjective lyricism.

Bakla: Would you say that your music was in some specific way linked up to Czech culture? (I'm not asking this as a routine duty question, but because I think that it is).

Smolka: I have often felt an affinity with the writers Hrabal and, when reading Svejk, Hašek. With their bizarre wry humour, which hides enormous kindness, and in the case of Hrabal, a potent nostalgia. But that probably couldn't be demonstrated in my work. Maybe I am just projecting my literary preferences onto my creations. Your question could only be answered by someone from as far as possible outside Czech culture. I am as far inside as possible – I'm as Czech as they come, I have always lived at one Prague address and if I take a trip 200 kilometres to the west I become half-illiterate, because I have never learned any foreign language properly. I am stuck inside my Czechness like in a cage, but I know Cage better than Czech music. I am definitely more connected to Feldman and Webern than to Feld and Eben.

Bakla: What are you really getting at as a composer?

Smolka: To answer that would sound banal or pompous and probably both. I'll do better to try to get at it than to define it in words.

Bakla: What are your most recent musical fascinations? What has surprised you or enchanted you?

Smolka: Unfortunately my capacity to be fascinated is weakening a little. But recently I was bowled over by Pavel Zemek's 4th Symphony and in general by his style over the last years, his exclusive concentration on unison. Encountering Gérard Grisey's last work, Quatre Chants Pour Franchir Le Seuil, was a fantastic overwhelming experience. There's a brilliant simplification there (relative, in relation to his earlier work), of the same kind that I love in Stravinsky's Requiem Canticles. I very much like Pärt's piece for strings, Orient Occident. I think that it's in this piece that he got his second wind, reviving his tintinnabuli with a freer approach. Twenty years late I have got to know deeper Ligeti's Horn Trio and I was immediately hooked. For the last four years I have been teaching 20th-century styles of composition at the Janáček Academy of Performing Arts and so I am being forced to study many things I believed I knew well again, and more deeply. And that is wonderfully enriching. I have been "rediscovering" Bartók and Messiaen, for example.