Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews (2000)

- Text: Henry David Thoreau

- Language: English

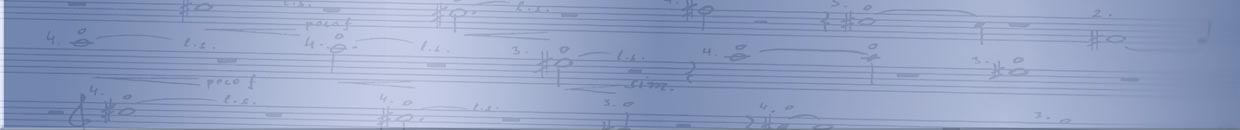

- Instrumentation: mixed choir (8S, 8A, 8T, 8B), 1 perc

- Movements: 5

- 1. Pleiades

- 2. Lake

- 3. Indians

- 4. Blackberries

- 5. Cypress

- Duration: 19'

- Commissioned by: SWR - Donaueschinder Musiktage

- Premiere: 22.10.2000, Donaueschinger Musiktage; SWR-Vokalensemble Stuttgart, Meinhard Jenne - perc., Rupert Huber - cond.

- Publisher: Breitkopf & Härtel (hire material)

- CD:

Program Note:

(EN) - short

Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews, a choir piece based on excerpts from Thoreau, focuses on transcendental aspects of Thoreau's text and their growing through his lyrical descriptions of nature's beauty. A very inspiring quality of these descriptions was a suggestive sound quality of Thoreau's English, which often became a starting point for my work. The piece is, along with Thoreau, a certain manifesto of simplified life closer to nature. Consequently I simplified my musical language and got closer to what I understand nature of music. Therefore this vocal piece handles with cantability, therefore the choir sings several times in unison or consonant harmonies, however, at the same time distorted by microintervals.

Martin Smolka

(EN) - long

I was asked to write a choir piece under the subject "a violence in our society" (in a widest sense). But I was attracted rather by violence which our society gives out - against nature, against our home-planet. And I prefered to be positive in my music rather than create a kind of protest-song. Intending to sing about a beauty of pure nature I decided to use excerpts of Thoreau's Walden. This book has fascinated me since years by surprisingly natural coexistence of very poetical descriptions of nature on one hand and very practical specifications of how Thoreau had lived in the woods and even how much it had cost, on the other hand.

Looking in the book for the excerpts I found out, that it had many more dimensions:

"The secret of existence"

Thoreau tends to relate all imaginable facts to the principle questions of existence, such as universe, religion and others, often quoting classical authors as well as the Bible, Confucius and other ancient Eastern wise men, and taking delight in mentioning the tradition of North American Indians. This aspect is perceptible in the choir piece in the beginning and end of the second movement ("Lake Walden is earth's eye"), in the last movement (meditation on freedom) as well as in the first movement (Pleiades):

"I discovered that my house actually had its site near to the Pleiades or the Hyades, to Aldebaran or Altair, dwindled and twinkling with as fine a ray to my nearest neighbour, and to be seen only in moonless nights by him."

(I often broke Thoreau's sentences and used just short fragments to have just limited musical material and to give only few brief impulses to listeners' imagination, as anyway man never understands more than few individual words in sung music. Here I quote the complete used fragments unbroken, writing also words which were not used in the music.)

"Green meadows of word’s sounds"

Discribing the beauty of lakes and woods, Thoreau works very musically with the English language. The whole sentences get under hegemony of one or two sounds, what help to evoke the described imagine with unexpected intensity. One sentence is filled with hissing sounds, another one with soft b, l and m and yet another one rings with plenty of r. This aspect was a starting point of the second choir piece "Lake":

"A lake is the landscape's most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth's eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature. The fluviatile trees next the shore are the slender eyelashes which fringe it, and the wooded hills and cliffs around are its overhanging brows. If you survey its surface, it is as smooth as glass, except where the skater insects scatered over its whole extent, by their motions in the sun produce the finest imaginable sparkle on it, or, a swallow skims so low as to touch it. It may be that in the distance a fish describes an arc of three or four feet in the air, and there is one bright flash where it emerges, and another where it strikes the water; sometimes the whole silvery arc is revealed; or here and there, perhaps, is a twistle-down floating on its surface, which the fishes dart at and so dimple it again. It is like molten glass cooled but not congealed and the few motes in it are pure and beautiful like the imperfections in glass."

(The imagine of the skater insects is expressed just by music ["tippy, tippy" etc.] without singing the words.)

"Mother Earth and Father Hurry"

The onomatopoeic aspect is used most remarkably in male-choir's sections of the 4th movement "Blackberries”. While the female choir sings calmly about the forest plants and fruits, the male choir alternates it with hectical activity, describing a planting of beans on a newly founded field.

"My beans attached me to the earth, and so I got strenght like Antaeus. This was my curious labor all summer - to make this portion of the earth's surface, which had yielded only cinquefoil, blackberries, johnswort, and the like, before, sweet wild fruits and pleasant flowers, produce instead this pulse.

Removing the weeds, putting fresh soil about the bean stems, and encouraging this weed which I had sown, making the yellow soil express its summer thought in bean leaves and blossoms rather than in wormwood and piper and millet grass, making the earth say beans instead of grass, - this was my daily work."

It is interesting that Thoreau, in the midst of 19th century, criticises the hurry of a modern civilisation: "Why should we live with such a hurry and waste of life?... We have the Saint Vitus dance and cannot possibly keep our heads still."

Thoreau’s main intention at Walden Pond was to live modestly, to spend just few time with looking for a living (two hours daily were enough, he says) and so get free to discern into the secret of things. Unfortunatelly there was no place left in my piece for this key metaphor:

"Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains. I would drink deeper; fish in the sky, whose bottom is pebbly with stars."

"What is freedom?"

Part 5, "Cypress", is based on Thoreau's quotation of Persian poet Sheik Sadi of Shiraz:

"They asked a wise man, saying: Of the many celebrated trees which the Most High God has created lofty and umbrageous, they call none azad, or free, excepting the cypress, which bears no fruit; what a mystery is there in this? He replied: Each has its appropriate produce, and appointed season, during the continuance of which it is fresh and blooming, and during their absence dry and withered; to neither of which states is the cypress exposed, being always flourishing; and of this nature are the azads, or religious indipendents. - Fix not thy heart on that which is transitory; for the Dijlah, or Tigris, will continue to flow through Bagdad after the race of caliphs is extinct: if thy hand has plenty, be liberal as the date tree; but if it affords nothing to give away, be an azad, or free man, like the cypress."

"A Violence and symphonic gradation"

Nice paradox of the work is that however I did not intend to reflect the violence made by man to another human being, the first fragment of Thoreau, which inspired me musically so that I wrote spontaneously quite quickly the whole movement, was the history of violence par excellence. In this 3rd part Jesuits found it's expression another aspect of Thoreau's writing: on certain places he becomes inflamed and his pathos grows similarly to symphonical gradation.

"The Jesuits were quite balked by those Indians who, being burned at the stake, suggested new modes of torture to their tormentors. Being superior to any consolation which be done by fell with less persuasiveness on the ears of those who, for their part, did not care how they were done by, who loved their enemies after a new fashion, and came very near freely forgiving them all they did."

I feel natural, that when writing a manifest of simplified way of life and of getting back to pure nature and to human being’s roots, I used simplified musical language, getting back to diatonic melodies and regular pulsing rhythm as well as consonant harmonies. The only sophisticated technic, which I used, where 1/4-tones and 1/6-tones detuning the minor or major triads. Its purpose is again a step back - to the special expressivity, which these detuned triads had in blues and other autentic folk music that was not played from scores.

In the end allow me one last quotation (or rather paraphrase). When I got close to the end of work on Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews (the title is made of Thoreau's words, too), a book by Julio Cortazar got into my hands. There I found a fitting designation of what I was doing: "When falling into bucolic swoon, the civilized people are lying; if they don’t get their scotch on the rocks at half past seven p.m., they would damn the minute, when they left their home to suffer through gad-flies, schorching heat and sunstroke and thorns and pricles."

Martin Smolka

H. D. Thoreau Walden, edited by Time Incorporated, New York 1962

(DE)

Ich wurde gefragt, ob ich zum Thema "Gewalt in unserer Gesellschaft" (im weitesten Sinne) ein Chorstück schreiben wolle. Aber mich berührte eher die Gewalt, die unsere Gesellschaft aussendet - gegen die Natur, gegen unseren Heimatplaneten. Und ich zog es vor, in meiner Musik positiv zu sein, statt eine Art Protestsong zu komponieren.

In der Absicht, über die Schönheit der reinen Natur zu singen, entschloss ich mich, Textausschnitte aus Thoreaus Walden zu verwenden. Dieses Buch hat mich seit Jahren fasziniert, besonders durch die überraschende Koexistenz sehr poetischer Naturbeschreibungen einerseits und ganz praktischer Spezifikationen von Thoreaus Leben in den Wäldern und sogar dessen Kosten andererseits.

Als ich das Buch nach Textausschnitten durchblätterte, fand ich heraus, dass es viele weitere Dimensionen hat:

"Das Geheimnis der Existenz"

Thoreau tendiert dazu, alle vorstellbaren Fakten mit den grundsätzlichen Fragen der Existenz in Verbindung zu bringen, Fragen zum Universum, zur Religion usw., indem er häufig antike Autoren, die Bibel, Konfuzius und andere Vertreter der östlichen Philosophie zitiert und sich darin gefällt, die Tradition der nordamerikanischen Indianer zu erwähnen. Diesen Aspekt verdeutlicht das Chorstück zu Beginn und gegen Ende des zweiten Satzes ("Lake Walden is earth’s eye"), im letzten Satz ("meditation on freedom") und im ersten Satz ("Pleiades"):

"I discovered that my house actually had ist site near to the Pleiades or the Hyades, to Aldebaran or Altair, dwindled and twinklin with as fine a ray to my nearest neighbour, and to be seen only in moonless nights by him."

["Ich entdeckte, dass mein Haus wirklich in der Nähe der Plejaden oder Hyaden bei Alderbaran oder Altair lag, und ein ebenso feiner Strahl wie von dort blitzte und glitzerte zu meinem Nachbarn hinüber und konnte nur in mondlosen Nächten von ihm gesehen werden."]

(Ich habe Thoreaus Sätze häufig auseinandergebrochen und nur kurze Fragmente benutzt, um das musikalische Material zu limitieren und um der Imagination des Hörers nur kurze Impulse zu geben - sowieso versteht man nie mehr als ein paar einzelne Worte in gesungener Musik. Hier zitiere ich die Ausschnitte vollständig, indem ich auch Worte wiedergebe, die in der Musik nicht verwendet werden.)

"Grüne Wiesen aus Wort-Klängen"

In seinen Beschreibungen der Schönheit von Seen und Wäldern arbeitet Thoreau sehr musikalisch mit der englischen Sprache. Ganze Sätze geraten unter die Vorherrschaft von ein oder zwei Klängen, was den beschriebenen Eindruck mit unerwarteter Intensität hervorruft. Ein Satz ist voller Zischlaute, ein anderer voller weicher Bs, Ls und Ms und wieder ein anderer klingelt mit vielen Rs. Dieser Aspekt war der Ausgangspunkt des zweiten Chorstücks "Lake":

"A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye: looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature. The fluvatile trees next the shore are the slender eyelashes which fringe it, and the wooded hills and cliffs around are its overhanging brows.

If you survey its surface, it is as smooth as glass, except where the skater insects scatered over its whole extent, by their motions in the sun produce the finest imaginable sparkle on it, or, a swallow skims so low as to touch it. It may be that in the distance a fish describes an arc of three or four feet in the air, and there is one bright flash where it emerges, and another where it strikes the water: sometimes the whole silvery arc is revealed; or here and there, perhaps, is a twistle-down floating on its surface, which the fishes dart at and so dimple it again. It is like molten glass cooled but not congealed and the few motes in it are pure and beautiful like the imperfections in glass."

["Ein See ist der schönste und ausdrucksvollste Zug einer Landschaft. Er ist das Auge der Erde. Wer hineinblickt, ermisst an ihm die Tiefe seiner eigenen Natur. Die Bäume dicht am Ufer, welche sein Wasser saugen und in ihm zerfließen, sind die schlanken Wimpern, die es umsäumen, und die waldigen Hügel und Felsen die Augenbrauen, die es überschatten. Betrachtet man aufmerksam die Oberfläche, so zeigt sich, dass sie so glatt wie Glas ist, ausgenommen dort, wo die über die ganze Seeausdehnung zerstreuten Wasserläuferinsekten durch ihre Bewegungen in der Sonne die denkbar feinsten Glitzerfunken hervorbringen oder eine Schwalbe tief genug herunterstreift, um das Wasser zu berühren. Hie und da beschreibt drüben ein Fisch einen Bogen von drei bis vier Fuß durch die Luft, und ein blendender Blitz zuckt auf, wo er herauskam, und dort, wo er wieder das Wasser traf; manchmal ist der ganze silberne Bogen zu sehen; oder hier und dort schwimmt ein Stück Distelwolle, nach dem die Fische schnappen, um so die Oberfläche wieder aufglitzern zu lassen. Der See sieht aus wie geschmolzenes, kühles, aber nicht erstarrtes Glas, und die Stäubchen darin sind rein und schön wie die Bläschen im Glas."]

(Der Eindruck der Wasserläuferinsekten wird nur durch die Musik wiedergegeben ["tippy, tippy" usw.], ohne dass die Worte gesungen werden).

"Mutter Erde und Vater Hast"

Der onomatopoetische Aspekt wird am deutlichsten in den Passagen für Männerchor im vierten Satz "Blackberries". Während der Frauenchor ruhig von den Pflanzen und Früchten des Waldes singt, durchbricht der Männerchor diesen Gesang mit hektischer Aktivität, indem er das Bohnenpflanzen auf einem gerade urbar gemachten Feld beschreibt.

"My beans attached me to the earth, and so I got strength like Antaeus. This was my curious labor all summer - to make this portion of the earth’s surface, which had yielded only ciquefoil, blackberries, johnswort, and the like, before, sweet wild fruits and pleasent flowers, produce instead this pulse.

Removing the weeds, putting frest soil about the bean stems, and encouraging this weed which I had sown, making the yellow soil express its summer thought in bean leaves and blossoms rather than in wormwood and piper millet grass, making the earth say beans instead of grass, - this was my daily work."

["Meine Bohnen banden mich an die Erde, und so empfing ich Kraft wie Antäus. Es war den ganzen Sommer durch meine sonderbare Beschäftigung, diesen Teil der Erdoberfläche, der bisher nur Fünfblattklee, Brombeeren, Johanniskraut und wildwachsende Beeren und zierliche Blumen hervorgebracht hatte, zu zwingen, jetzt diese Hülsenfrucht zu tragen.

Das Unkraut auszujäten, frische Erde um die Bohnenpflanzen zu häufeln und das Kraut, das ich gepflanzt hatte, zum Wachsen aufzumuntern, den gelben Boden zu veranlassen, seinen sommerlichen Gedanken in Bohnenblättern und Blüten statt in Wermut, Pfeifenkraut und Hirsegras Ausdruck zu verleihen, die Erde Bohnen sprießen zu lassen statt Gras - das war meine tägliche Arbeit."]

Es ist interessant, dass Thoreau Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die Hast der modernen Zivilisation kritisiert: "Warum sollten wir mit einer solchen Hast leben und Leben vergeuden? ... Wir haben den Veitstanz und können unsere Köpfe nicht still halten."

Thoreaus Hauptintention am Waldensee war, bescheiden zu leben, nur ein wenig Zeit für den Lebensunterhalt zu opfern (zwei Stunden täglich seien genug, fand er) und so frei zu sein, "um den Geheimnissen der Dinge nachzugehen". Unglücklicherweise hatte ich in meinem Stück keinen Platz mehr für diese Schlüssel-Metapher:

"Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains. I would drink deeper; fish in the sky, whose bottom is pebbly with stars."

["Die Zeit ist nur ein Fluss, in dem ich fischen will. Ich trinke daraus, aber während ich trinke, sehe ich seinen sandigen Grund und entdecke, wie seicht er ist. Seine schwache Strömung verläuft, aber die Ewigkeit bleibt. Ich möchte in tieferen Zügen trinken, im Himmel fischen, dessen Grund voll Kieselsterne liegt."]

Was ist Freiheit?

Teil 5, "Cypress", basiert auf Thoreaus Zitat de persischen Dichters Scheich Saadi von Schiras:

"They asked a wise man, saying: Of the many celebrated trees which the Most High God has created loftly and umbrageous, they call none azad, or free, excepting the cypress, which bears no fruit: what a mystery is there in this? He replied: Each has its appropriate produce, and appointed season, during the continuance of which it is fresh and blooming, and during their absence dry and withered; to neither of which states is the cypress exposed, being always flourishing; and of this nature are the azads, or religious independents. - Fix not thy heart on that which is transitory; for the Dijlah or Tigris, will continue to flow through Bagdad after the race of caliphs is extinct: if thy hand has plenty, be liberal as the date tree: but if it affords nothing to give away, be an azad, or free man, like the cypress."

["Sie fragten einen weisen alten Mann und sprachen: Von den vielen herrlichen Bäumen, die der höchste Gott hoch und schattenspendend erschaffen hat, wird keiner azad oder frei genannt außer der Zypresse, die keine Früchte trägt. Was für ein Geheimnis ist das? Er antwortete: Jeder hat seinen eigenen Ertrag und seine Zeit, während der er frisch und blühend dasteht, und wenn sie vergangen ist, trocknet er und welkt; nicht so ergeht es der Zypresse, die immerwährend grünt; von dieser Art sind die Azads, die religiös Unabhängigen. - Hänge nicht dein Herz an das, was vergeht; denn der Dijlah oder Tigris wird noch durch Bagdad fließen, nachdem der Stamm der Kalifen erloschen ist. Ist deine Hand voll, so sei freigebig wie der Dattelbaum, besitzt sie aber nichts zum Verschenken, so sei ein Azad, ein freier Mann, wie die Zypresse frei ist."]

"Gewalt und symphonische Steigerung"

Das Werk enthält eine schöne Paradoxie, die darin liegt, dass, obwohl ich nicht vorhatte, die Gewalt von Menschen gegen Menschen zu reflektieren, der erste Textausschnitt von Thoreau, der mich musikalisch inspirierte, so dass ich den ganzen Satz ziemlich schnell komponierte, die Geschichte der Gewalt par excellence erzählt. In diesem dritten Teil "Jesuits" kommt noch ein anderer Aspekt in Thoreaus Schreiben zur Sprache: an manchen Stellen erregt er sich so sehr, dass sein Pathos wie in einer symphonischen Steigerung wächst.

"The Jesuits were quite balked by those Indians who, being burned at the stake, suggested new modes of torture to their tormentors. Being superior to any consolation which the missionars could offer; and the law to do as you would be done by fell with less persuasiveness on the ears of those who, for their part, did not care how they were done by, who loved their enemies after a new fashion, and came very near freely forgiving them all they did."

["Die Jesuiten wurden ganz beschämt durch jene Indianer, welche, als sie am Pfahle verbrannt wurden, ihren Folterknechten neue Folterqualen vorschlugen. Da sie über physisches Leiden erhaben waren, kam es manchmal vor, dass sie auch über jede Tröstung erhaben waren, welche ihnen die Missionare zu bieten hatten; und das Gesetz, welches gebietet, das zu tun, was man wünscht, dass einem selbst getan werde, berührte mit weniger Überzeugungskraft die Ohren derjenigen, denen es einerlei war, was man ihnen tat, die ihre Feinde auf eine neue Weise liebten und nicht weit davon entfernt waren, ihnen alles, was sie taten, zu vergeben."]

Ich finde es natürlich, dass ich, wenn ich ein Manifest über eine vereinfachte Lebensweise schreibe und über die Rückkehr zur Natur und zu den Wurzeln des Menschseins, auch eine vereinfachte musikalische Sprache verwende und zu diatonischen Melodien und regelmäßigen Rhythmen ebenso wie zu konsonanten Harmonien zurückkehre. Die einzige verfeinerte Technik, die ich verwendet habe, sind die Verstimmungen der Moll- oder Durdreiklänge um Viertel- und Sechsteltöne. Die Absicht liegt hier wiederum in einem Rückwärtsschritt - zu jener speziellen Expressivität, die diese verstimmten Dreiklänge im Blues besaßen oder in anderer authentischer Volksmusik, die nicht von Noten gespielt wurde.

Erlauben Sie mir, zum Schluss ein letztes Zitat (bzw. eher eine Paraphrase). Als ich die Arbeit an Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews (auch der Titel besteht aus Ausdrücken Thoreaus) beinahe beendet hatte, fiel mir ein Buch von Julio Cortazar in die Hände. Darin fand ich eine passende Beschreibung für das, was ich tat: "Wenn sie in eine bukolische Ohnmacht fallen, lügten die zivilisierten Menschen: wenn sie nicht abends um halb acht ihren Scotch on the rocks kriegen, verfluchen sie den Augenblick, in dem sie ihr Haus verlassen haben, um unter Viehbremsen, brütender Hitze und Sonnenstich und Dornen und Stacheln zu leiden."

Martin Smolka

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen: Lydia Jeschke

Die Übersetzung folgt der Ausgabe: H. D. Thoreau Walden oder Leben in den Wäldern, Zürich: Diogenes Verlag 1979.

(FR)

On m’a demandé si je voulais écrire une pièce pour chœur sur la thème de «la violence dans notre société» (au sens large). Or, davantage me touche la violence venant de notre société et dirigée contre la nature, contre notre planète. Je préfère être positif dans ma musique, pltôt que de composer une sorte de protestation.

Comme j’avais l’intention de chanter la beauté de la nature pure, j’ai décidé de reprendre des fragments du Walden de Thoreau. Ce livre me fascine depuis des années, notamment parce que des descriptions très poétiques de la nature y côtoient des aspects spécifiques et très pratiques sur les goûts de l’auteur et sa vie dans les bois.

En feuillentant le livre à la recherche d’extraits, j’ai découvert quantité d’autres dimensions:

Le secret de l’existence

Thoreau rattache tout ce qui se conçoit à des questions fondamentales sur l’existence, sur l’univers, sur la religion etc., en citant souvent des auteurs anciens, la Bible, Confucius et d’autres noms de la philosophie orientale, tout en aimant à évoquer les traditions des Indiens d’Amérique du Nord. La pièce pour chœur évoque cet aspect au début et vers la fin du deuxième mouvement (Lake Walden is earth’s eye), dans le dernier mouvement (meditation on freedom) et dans le premier mouvement (Pleiades):

«Je découvre que ma maison est toute proche des Pléiades ou des Hyades, près d’Aldebaran ou d’Altaïr ; un fin rayon, comme venu de là-bas, scintillait en direction de mon voisin, et lui seul pouvait le voir dans les nuits sans lune.»

(J’ai souvent décomposé les phrases de Thoreau et utilisé quelques fragments seulement, afin de limiter le matériau musical et ne donner à l’imagination de l’auditeur que de brèves impulsions – la musique chantée ne permet de toute façon jamais de comprendre plus que quelques mots. Je cite ici les passages dans leur intégralité ; certains mots ne sont pas repris dans la musique.)

Vertes prairies de sonorités verbales

Lorsqu’il dépeint la beauté des lacs et des forêts, Thoreau travaille de façon très musicale sur la langue anglaise. Des phrases entières sont dominées par une ou deux sonorités, ce qui crée une intensité inattendue dans l’impression décrite. Une phrase est pleine de sons sifflés, une autre pleine de doux b, m ou l, puis une autre pleine de r. Cet aspect constitue le point de départ de la deuxième pièce pour chœur Lake:

« Le lac est trait le plus beau et le plus expressif d’un paysage. Il est l’œil de la terre. Celui qui regarde au-dedans mesure la profondeur de sa propre nature. Les arbes sur les rives, qui s’abreuvent de son eau et se mêlent à lui, sont les cils qui le bordent, les collines et roches boisées, les sourcils qui le surplombent.

Si l’on contemple la surface avec attention, elle apparaît lisse comme du verre, sauf en ces endroits où de petits insectes, disséminés un peu partout, effectuent pour avancer un mouvement que le soleil transforme en infimes scintillements, où bien lorsqu’une hirondelle descend suffisamment bas pour effleurer l’eau. Ci ou là, un poisson décrit en l’air un arc de trois à quatre pieds, formant un éclair aveuglant là où il surgit et là où il disparaît à nouveau sous l’eau ; parfois même l’arche argentée est entièrement visible. Il arrive que flotte ici ou là une boule de chardon, qu’attrapent des poissons dans un nouvel éclair. Le lac ressemble à de la glace fondue, froide, mais pas figée. Les petites poussières y sont aussi belles et pures que des gouttelettes dans l’herbe.»

(Le son des insectes à la surface de l’eau n’est rendu que par la musique – tippy, tippy etc. – sans que les mots soient chantés.)

Terre Mère, Père Empressement

C’est dans les passages pour chœurd’hommes du quatrième mouvement, Blackberries, que l’aspect onomatopoétique est le plus clair. Tandis que le chœur de femmes chante calmement les plantes et les fruits, le chœur d’hommes rompt ce chant avec frénésie en décrivant des plantations de haricots dans un champ rendu arable.

«Mes haricots me rattachaient à la terre, qui me donna la force d’Antée.

Ce fut tout au long de l’été une marveilleuse activité que de contraindre à engendrer ces fruits une contrée de la terre qui n’avait donné jusque-là que du trèfle, des mûres, des baies sauvages, du millepertuis et de petites fleurs.

Arracher la mauvaise herbe, répartir de la terre fraîche autour des plants, encourager les semences à pousser, inciter le sol jaune à exprimer la douceur de l’été par des feuilles et fleurs de haricots et non par l’armoise ou le millet, faire éclore des fruits et non de l’herbe – tel était mon travail quotidien.»

Il est intéressant que Thoreau, à la moitié du XIXe siècle, critique de la civilisationmoderne: «Pourquoi vivre avec tant d’empressement et gaspiller la vie?... Nous avons la danse de Saint-Guy et ne pouvons plus apaiser nos esprits.»

En vivant dans les bois, Thoreau entendait vivre modestement, ne consacrer que peu de temps à subvenir à ses besoins (selon lui, deux heures par jour suffisaient) et, ainsi, être libre «pour sonder le secret des choses». Malheureusement, je n’avais plus la place pour cette métaphore clé dans mon morceau:

«Le temps est un fleuve dans lequel je veux seulement pêcher. Je m’y abreuve, mais tout en buvant, je vois le fond sableux et découvre qu’il est peu profond. Il s’écoule faiblement, mais l’éternité reste. Je voudrais boire plus profondément, pêcher dans le ciel, dont les graviers sont des étoiles.»

Qu’est-ce que la liberté?

La cinquième partie Cypress s’inspire d’une citation du poète persan Sheikh Saadi de Shira reprise par Thoreau:

«Ils interrogèrent un vieil homme sage et dirent : de tous les arbres merveilleux que le Dieu des Dieux a créés pour dispenser de l’ombre, nul n’a le nom d’Azad à part le cyprès qui ne porte pas de fluits. Quel en est le secret ? Il répondit : tous ont leurs fruits, ils sont frais et fleurissent un temps, mais une fois ce temps écoulé, ils sont secs et fanés. Le cyprès, lui, est toujours vert, de même il en va des Azad et de leur indépendance religieuse. N’attache pas ton cœur à ce qui est éphémère; le Tigre et l’Euphrate traverseront encore Bagdad, lorsque la lignée des califes se sera éteinte. Si ta main est pleine, sois aussi généreux qu’un dattier, si elle n’a rien à offrir, soit un Azad, un homme libre, libre comme le cyprès.»

Violence et progression symphonique

L’œuvre contient un paradoxe intéressant: bien que je n’aie pas l’intention d’évoquer la violence des hommes contre les hommes, l’extrait de Thoreau qui m’inspira musicalement, et me permit de composer assez vite tout le premier mouvement, raconte l’histoire de la violence par excellence. Dans cette troisième partie «Jesuits» s’exprime une autre idée décrite par Thoreau: dans certains passages il s’enflamme tellement que son pathos croît comme une progression symphonique.

«Les Jésuites furent humiliés par les Indies, qui, brûlés au pilori, proposèrent de nouveaux supplices à leurs tortionnaires. Etant au-dessus de toute souffrance physique, il arrivait qu’ils fussent également au-delà de toute consolation que leur proposaient les missionnaires. Et la loi qui ordonne de faire à autrui ce que l’on souhaiterait pour soi-même n’effleurait qu’avec peu de conviction les oreilles de ceux à qui n’importait guère ce qu’on leur faisait, qui aimaient leurs ennemis d’une nouvelle façon et n’étaient pas loin de pardonner tout ce qu’ils faisaient.»

Si j’écris un manifeste sur la vie simple, sur le retour à la nature et aux sources de l’humanité, il est à mon sens tout naturel que j’utilise un langage musical simple, que je revienne à des mélodies diatoniques, des rythmes réguliers et des harmonies consonantes. Ma seule technique plus raffinée consiste à désaccorder la tonalité de mineur, ou les accords de majeur d’un quart ou sixième de tons. Mon intention isi est de suggérer cette expressivité spécifique des «accords désaccordés» du blues ou d’autres musiques populaires originales qui ne sont pas jouées en notes.

Permettez-moi une dernière citation pour finir (ou plutôt une paraphrase). Alors que j’avais presque terminé le travail sur Walden, the Distiller of Celestial Dews, un livre de Julio Cortazar m’est tombé entre les mains qui donnait une description adaptée de ce que je faisais: «Lorsqu’ils sombrent dans la pâmoison bucolique, les hommes civilisés mentent: si le soir, à sept heures et demi, ils n’ont pas leur scotch on the rocks, ils maudissent l’instant où ils ont quitté leur maison pour ebdurer les bêtes, la chaleur accablante, les insolations, les ronces et les broussailles.»

Martin Smolka

Traduction de l’allemand : Martine Passelaigue

Reviews:

Reinhard Schulz, NMZ, Auszug aus dem Turm

(...) Es mag bezeichnend für die ganzen diesjährigen Donaueschinger Musiktage sein, dass im gleichen Konzert, vor den terroristischen Attacken Kreihsls und Neuwirths ein Chorstück nach Thoreau des Pragers Martin Smolka stand, das in seiner Natur- und Schönheits-Begierde polar entgegengesetzt war: „Walden, The Distiller of Celestial Dews“. Smolka merkte an: „Das Stück basiert auf David Thoreaus berühmtem Buch ‚Walden‘. Es ist eine Art Manifest über ‚Zurück zur Natur‘ und über die Vereinfachung der Welt – aber nicht nur dies, sondern auch über die Wiederbelebung der inneren Kraft menschlichen Seins, über die Verbindungen zu den natürlichen Quellen, zum Universum. Das ganze Buch spricht davon und meine musikalische Sprache versucht auch zu vereinfachen, hin zum Singen, zu schönen Klängen, jedoch ohne musikgeschichtliche Klischees zu wiederholen.“ Es waren wunderbar einfache, tonal simple Linien, zugleich horrend schwer vorzutragen. Denn sie waren mikrotonal leicht verschoben, zum Beispiel durch Sechsteltöne, die dem SWR-Vokalensemble unter Rupert Huber alles abforderten. Thoreaus Forderung nach sich selbst entäußernder Einfachheit, die zugleich ein Extrem an innerer Kraft verlangen, zog auf diese Art direkt in die musikalische Sprache ein. (...)

Listen to an mp3 excerpt 1

Listen to an mp3 excerpt 1